Interested in Rehab/Relining?

Get Rehab/Relining articles, news and videos right in your inbox! Sign up now.

Rehab/Relining + Get Alerts"Evolve or Die!”

That’s the challenge that drives John Smallis, public works superintendent at Thousand Oaks, Calif. As a result, his city’s wastewater collection system is very much alive and well.

“It’s the headline of an article I have taped to my office wall,” explains Smallis of the exhortation. “It’s the way we operate. We continue to make improvements in response to the numerous issues that many wastewater collections systems face.

“Changes take time,” he advises, “but when well planned, they result in immediate benefits in the form of reduced labor, improved safety and better system operation.”

A planned city

Thousand Oaks is located in southeastern Ventura County — northwest of the Los Angeles metropolitan area — and is home to 127,000 people. The city was master-planned by a private investment company in the 1950s, incorporated in 1964, and is one of the few communities that has adhered to its master plan throughout its development.

The sewer system consists of 550 miles of pipe and 8,500 manholes. There are no combined sewers, and only two lift stations. Wastewater is conveyed to the tertiary level Hill Canyon Wastewater Treatment Plant, which reclaims and recycles about 10.5 million gallons a day. The collection system is part of the city’s Wastewater Division and is based at the Thousand Oaks Municipal Service Center, which houses all public works activities.

Even though the infrastructure is relatively new, Smallis and his team face challenges that are common to collections departments across the U.S.

“While we’re lucky to have newer systems, we still have a lot of vitrified clay pipe and a lot of brick manholes,” he says. “Hydrogen sulfide eats away at these surfaces, just as it does elsewhere.”

And, as one might imagine from its name, Thousand Oaks has a plethora of trees and this leads to problems with roots. It’s also led to a solution that’s representative of the way the Thousand Oaks crew tackles challenges.

“We used to cut roots by hand,” explains Smallis. “We’d do as many as 200 manholes in a year, chopping out roots and picking them up and removing them. Then we looked at how we could improve the process.”

With the support of the city council and the requisite budget, the collections division started chemical foaming its lines and using new jetting heads to clear roots.

“We evaluated the chemical expense, and chose to outsource the foaming,” says Smallis. “We use Duke’s Root Control, and they guaranteed no roots for three years. We also evaluated the cutting heads we were using,” Smallis says.

Root control has become an operating standard as Thousand Oaks goes about relining its older sewer sections using resin-impregnated material.

“We TV the areas where we’re having trouble focusing on the older sections first,” says Smallis. “Then we foam those sections before we reline. We did more than 25,000 feet last year.”

Smallis says the approach saves time.

“We used to go back six or seven times in one run,” he says. “Now, we do one pass and we have no roots. They’ve been reduced tremendously.”

Utilities supervisor John Nelson confirms the choice of cutter heads. In the old days, they used their combination trucks with jetting nozzles for roots, but that required multiple runs. He says another cleaning approach was “balling” — using water pressure to push a scouring ball down the line. “It might take us 30 to 45 minutes to do 300 or 400 feet,” he says, “and we’d use a lot of water.”

The new heads are high-tech, stainless steel with ceramic inserts. Says Nelson, “They last longer, use less water, and cut more efficiently, resulting in more footage cleaned.

“While there are numerous heads available on the market, we would call in vendors and ask if we could demo their specialty nozzles for a couple of weeks before buying them. The staff found the ones they liked best and for a minimal cost, we purchased them (Warthog nozzles from StoneAge, Chain Flail cutters from Shamrock Pipe Tools, Milling Machine cutters from USB – Sewer Equipment Corp.).

“It really depends on your equipment and your system to determine which nozzles are best for your operations,” he concludes.

Reduced I&I

A measurable reduction in inflow and infiltration is another important benefit of the new cleaning method.

“Thousand Oaks has pockets of high groundwater,” explains Smallis. “When it rained, we would get a heavy inflow to the treatment plant, and it would last a long time — trailing off for more than a month as the groundwater levels slowly subsided.

“The pipeline improvements have had an immediate impact. Our flowmeters are radar based, non-contact (Hach) and show the initial flow quickly dropping off within days, not months.

“That’s directly attributable to our sewer and manhole lining. The costs have been more than recovered by reductions in the treatment expense.” Thousand Oaks has used National Liner, Insituform and SAK Construction for sewer lining. Zebron, Sancon, Socal Pacific and National Coating & Lining Co. have performed manhole rehabilitation.

Smallis says investment in new flowmeters has also helped. “We’re moving to Hach’s Flo-dar models,” he explains.

IT advances

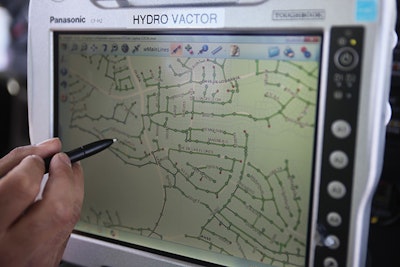

The most significant change at Thousand Oaks, however, is computerization, and it’s completely transformed how the wastewater collections team does business.

“The move really began back in 2002,” explains Smallis. “We had a long-tenured work force who were used to doing things on paper. Our goal was to take that activity to the next level — ideally a paperless approach based on best management practices. We needed to get past the paperwork hurdle and move on to computers.”

The project really took off in 2006, when Brian Hetherington was hired as a senior IT technician, and was charged with computerizing the division’s maintenance management system and developing GIS-based asset management.

At first, Hetherington organized a pilot project that placed laptop computers in two of the division’s trucks. An early issue was vibration in the vehicles, but the concept proved workable.

“We started simple,” says Hetherington. “We changed work orders from paper to electronic versions in the individual trucks. Next, we leveraged the program into a computerized management and maintenance system (CMMS). It took about a year for us to work out the bugs, but in 2008-2009 we placed laptops in all our hydro trucks.”

As a result, all work orders are decentralized into the trucks, and the CMMS system tracks staff time, labor actions, and costs — an ideal tool for analysis and tracking where the division is spending its time and money.

“We’re able to trace visually where we’ve cleaned,” explains Hetherington. “We use touch screens from iWater (infraMAP software). It integrates GIS and our CMMS.”

Next steps in Hetherington’s plan include using tablets instead of laptops. “We’ll have two tablets in each truck — completely decentralized and wireless, and very user friendly. The last thing an operator needs is a complicated work order system that slows them down. We’ve integrated our GIS with our CMMS program.”

Smallis says there is no book outlining how to undertake this type of technology upgrade. “We learned by going to conferences, talking with others, and communicating with our own staff,” he says. “What you can do depends on the budget available, but you can take small steps, make small improvements.”

The cameras and images used by the Thousand Oaks crew are an example. “We started with Polaroid cameras for our staff inspections in the field,” Smallis recalls, “but now we use digital cameras. We can zoom in, maintain high quality (images) and store them in a terabyte-sized memory that’s large enough to record everything.

“It’s the next step; we were able to take our staff from by-hand records to all digital in a very short period of time.”

Staff buy-in

As any organization embraces new technology and leaps ahead it must bring its employees along with it, and that’s not always easy.

“None of this would be possible if it were not for staff buy-in, as well as a solid budget, open management and our continued desire to improve our service,” says Smallis.

“It’s difficult. One group (of employees) comes in with computer skills, but another group has never been exposed to that, except what they learn on the job.”

He says honesty and communications are key.

“You have to make your expectations known right up front,” he says. “Discuss with the group exactly where we want to go. No sugar-coating.”

In addition, Smallis advocates achieving small successes and being unafraid to fail.

“It’s easier to move forward with change if you have small successes,” he says. “Once in a while you’re going to fail,” he says. “You need to continue to move forward toward your overall goal.

“Quick fixes don’t work,” he adds, noting that organizations need long-term vision and commitment from the staff. “We’re lucky to have long-term employees with great knowledge of the systems. That’s a big advantage in our vision for change.”

Smallis and the Thousand Oaks team believe that once created and nourished, the environment for change becomes contagious.

“Ideas start coming in from all over the place,” he says.