Interested in Rehab/Relining?

Get Rehab/Relining articles, news and videos right in your inbox! Sign up now.

Rehab/Relining + Get AlertsMortar missing between manhole risers in Zieglerville, Pa., created large gaps through which Perkiomen Creek poured when flooded. Flows frequently exceeded the 200,000 gpd discharge limit at the sewage treatment plant.

"Surprisingly, we didn't have overflows or manholes backing up," says Public Works director Tom Manning. "By speeding up the treatment process, all the water went through the plant, but it was touch and go."

Lower Frederick Township, the municipality governing the village, had limited success in reducing inflow and infiltration (I&I). Without substantial improvement, the 4,800 residents faced constructing a larger treatment plant, a solution they couldn't afford.

While attending a state wastewater conference, Manning found the Multiplexx PVCP cured-in-place manhole lining system from Terre Hill Composites. Between 2006 and 2011, the township spent $228,000 to install 40 liners, patch 14 leaks, and replace risers, frames and covers on 40 more manholes.

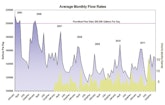

The efforts reduced average flows by 30,000 gpd and three-month peak average flows by 50,000 gpd. Based on an estimated treatment cost of 0.6 cents per gallon, the reductions represent an annual savings of $70,000.

Initial efforts

The township has 25 miles of 8- to 12-inch PVC sanitary sewers, installed in 1978, and 350 48-inch brick cone and precast manholes 3 to 15 feet deep. The sewage plant, which was upgraded in 2003, treats an average of 150,000 gpd using Purestream AER-O-FLO extended aeration tanks and a Schreiber clarifier.

The upgrade also required a new lift station at the plant. During a high water episode, Manning opened the wet well and noticed huge maple leaves floating on the surface. "That got us looking at five manholes along the creek where we found the grout missing between the covers and structures," he says.

In December 2006, a contractor rehabilitated the manholes with PAMTIGHT watertight ductile iron covers and polyethylene seating rings. Workers also grouted frames to risers. "For five years, the area didn't flood and we never knew if the covers worked," says Manning. "In 2011, two back-to-back tropical storms proved that they did."

In most manholes, however, infiltration was the problem. High groundwater pressure caused 5/8-inch-diameter streams of water to jet across some structures, bringing in 10,000 gpd. "From 2000 to 2005, a contractor grouted all the manholes and repaired bad saddle connections on the PVC pipes," says Manning. "We learned that grouting just moved the leaks somewhere else."

Long-term solution

Manning took the manhole lining system literature from the conference to Carol Schuehler, P.E., the township engineer with Urwiler and Walter. "A big selling point for us was the 10-year non-prorated warranty on the liners against failure, including leaks and corrosion," she says. "Standard contracted leak repairs have a one-year maintenance bond."

In 2007, the township issued one contract for standard repairs and another for 10 liners installed by Terre Hill Composites. "The following year, the grouted manholes were leaking again, so we switched completely to the PVCP-F liners," says Manning.

According to Terre Hill president William Oberti, PVCP-F stands for PolyVinyl Chloride with Polyester fleece and Fused seams (the plastic is welded into a monolithic structure). The composite liners have 25 mils of PVC on the exposed side fused with fleece on the back side, and layers of woven roving fiberglass mat between the PVCP and structure substrate. The liners for Lower Frederick averaged 139 mils thick.

Workers from Terre Hill Composites measured the manholes from the top casting to the flow-channel invert before fabricating the custom liners. They arrived on-site in the installation truck housing a 1,000-gallon water tank, air compressor, 5,000 psi/4 gpm pressure washer, 17 kW generator, 15 hp electric blower, and a 400,000 Btu, 2.7 gpm oil-fired water heater producing 320-degree water.

Under pressure

Workers cleaned the manholes, cut away protrusions and steps, patched as needed, and plugged above bench inlets. They sealed infiltration points using non-shrink cementitious grouts, hydraulic cements, and, for heavy leaks, pump Aqua Seal, a dual-component hydrophobic polyurethane chemical grout.

"The walls don't have to be dry before we line," says Oberti. "Under pressure, the 100-percent solids, VOC-free hydrophobic epoxies we use will force residual moisture out of the way."

After laying plastic on the ground, the crew impregnated a liner with the epoxy blend, attached it to an installation manifold, and used a crane on the back of the truck to lift and lower it into the manhole. Although the liner could hold air and pressure on its own, workers inserted an inflation bladder as a fail-safe measure through the manifold, which resembles an inverted tuna can. Ratchet straps sealed the liner around the can, which has ports for air and heat, an outlet pipe, and gauges in the lid.

"Inflating and pressurizing the liner forces the epoxy into the substrate, creating mechanical anchors in the substrate so the liner becomes one with the host as the epoxy cures," says Oberti. Introducing vaporous water into the bladder at 200 degrees F and holding the pressure at 3 psi cured the epoxies in about 60 minutes. A valve controlled pressure and heat by limiting the vapor escaping through the outlet pipe.

Professional touches

Once the liner cured, workers removed the lid and lowered a submersible pump to remove 300 to 400 gallons of condensate. They reinstated the inlets and outlets with a 6-inch blade on a reciprocating saw. "Laying the blade flat gives us a tapered cut," says Oberti. "Although it's a sealed interface, we still dress the edges with a silica mastic we manufacture. It's heavy in glass to ensure the edges are as robust against hydrogen sulfide as the PVC interior."

Installations took four to five hours, and Terre Hill inserted two liners per day. Afterward, Manning no-ticed infiltration drop by 40,000 gpd.

The township originally requested the non-invert lining system in which the channel remained open and flow continued under the liner. Workers plugged the main inlet line and bypassed the flow as needed. "We found leaks in the channels when we inspected them the following spring," says Manning. "From then on, we went with invert lining."

According to Oberti, the invert lining system has enough material for workers to shape the liner around the channel and down to the invert, then up and across the bench to the walls. Manning found no more leaks.

The results the township has seen since the installations have justified the expense. In 2010, plant flows exceeded the permit level on 12 days; a 62.5 percent reduction from 32 days in 2006. In 2011, rainfall was more than 50 percent higher than normal and included Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee, yet only 14 days were over the limit.

"Standard leak repairs cost $925 per manhole and must be repeated every two or three years," says Schuehler. "Liners cost $3,470 each, but last 10 years or more. Besides the annual savings in treatment costs, they saved us $8 million by delaying the necessity for a new treatment plant."