Researchers at the University of Kansas School of Engineering are set to begin a two-year project aimed at creating models using projected climates to help state officials better allocate water.

The idea came a few years ago when Josh Roundy, associate professor of civil, environmental and architectural engineering at KU, met with a representative from the Kansas Water Office and together realized the need for more in-depth models depicting water availability in different climate scenarios.

A proposal was drawn up and eventually chosen to receive funding from the Bureau of Reclamation’s WaterSMART grant with additional funds from KU and the KWO.

The proposed research will expand the models currently used by the KWO that are largely based on data recorded during a 1950s drought. Roundy thinks the outcome of this project will make it possible for officials to consider different scenarios besides drought by looking forward to climate predictions and their direct impact on evaporation and streamflow. The proposed project will do just that and ultimately help with future water allocation decisions in Kansas.

“Because of my degree in civil engineering, I’m very interested in working with people and infrastructure,” Roundy says. “I want to make the data that we work on as climatologists useful in terms of making better decisions. That’s always been the motivation for why I do what I do.”

Scope

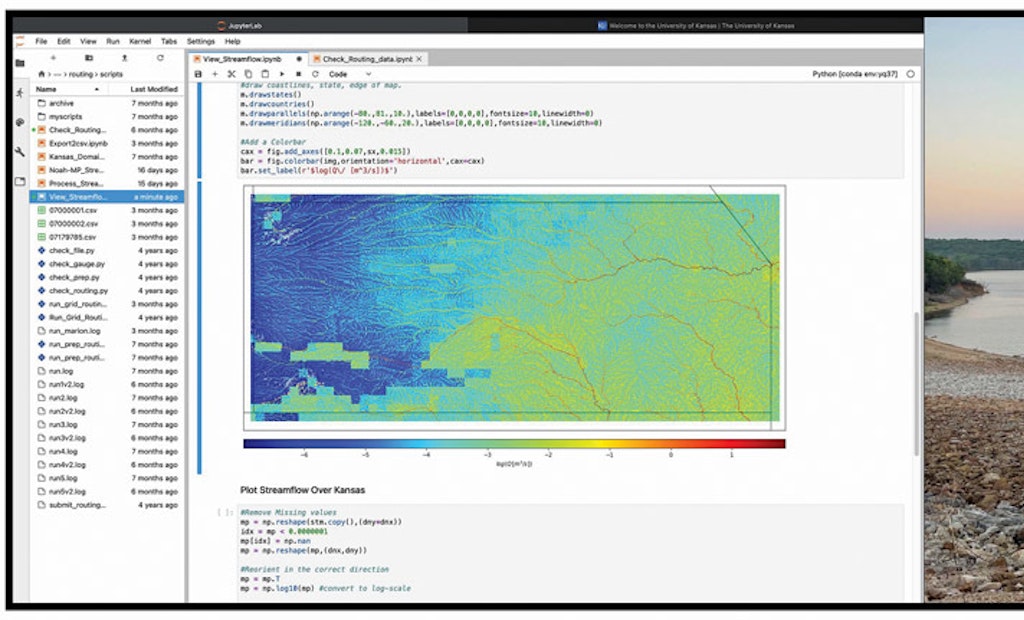

The project is localized to the central and eastern portions of Kansas and incorporates six river basins, 21 reservoirs, 51 inflows and 163 sources of consumptive water use. The team, led by Roundy, will use the Couple Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 from the World Climate Research Programme to forecast how climate changes will impact rainfall and water availability in upcoming years. These models compare multiple emission scenarios along with responses from the land, ocean and atmosphere.

“We’re going to be taking down-scaled climate scenarios, which the Bureau of Reclamation has already done for all of the U.S., and using those, we will be running a model that is going to calculate stream flow and evaporation,” Roundy says. “So, we will model what that type of data looks like under different climate scenarios. The challenge is then to be able to validate that our hydrologic model that we’re using is giving us useable results.”

Roundy says they will spend a lot of time validating, calibrating and checking the values they get from the hydrologic models compared to those observed in the past.

Though this work will focus on Kansas specifically, the strategy used and the ending results may benefit municipalities across the country. “More broadly speaking, I think municipalities will be more inspired to actually take on using climate data in different scenarios and use that in their planning and maybe not be so intimidated by it,” Roundy says.

That part of the project is important. Compiling data into models is only useful for the KWO and other utilities if it’s in a form and presented in a way that is easily understood. “The whole idea behind this is that we can come up with ways to do that processing and put it in a way that’s simple for the Kansas Water Office to put in their model. To remove that technical barrier, so more people can use that data.”

Broader reach

It’s Roundy’s goal that the project will result in a published academic paper showing other states and regions an approach for forecasting future water supplies, providing an extra tool to scheme and adjust future water distribution plans.

Another challenge for Roundy and his team is the fact that their research is dependent on a very unpredictable field of data. “Climate data is very uncertain. We are trying to form this uncertainty in a way that can still be very useful,” Roundy says. What he means is that even though their estimates might not be completely accurate, the work could still offer a level of risk assessment for water supply; it just comes down to displaying it in the right way.

Managing water supplies may become more and more challenging in upcoming years as increased periods of drought are projected as well as periods of increased flooding. Generating scenarios based off climate changes like more frequent droughts and flooding and how the seasonality may change are the types of models that could exponentially help local authorities make educated decisions moving forward.

“I think there are a lot of applications for climate scenario data,” Roundy says. “The ultimate goal is to help make water allocation more sustainable long term and to help the Kansas Water Office make good decisions about allocation into the future while encouraging conservation and being all around smarter with our water.”