Interested in Flow Control?

Get Flow Control articles, news and videos right in your inbox! Sign up now.

Flow Control + Get AlertsAfter 22 months without a combined sewer overflow, the Milwaukee (Wis.) Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD) was forced to conduct two in the past two weeks when rainstorms pounded Southeastern Wisconsin.

“We got to the point where we had to either have an overflow or overfill the system and if we overfill the system, that increases the risk of basement backups in the region,” says Kevin Shafer, MMSD executive director.

The first combined sewer overflow was conducted between 6:40 a.m. on April 10 and 6:10 a.m. on April 13. The total CSO was estimated at 594 million gallons for the first overflow.

The second lasted from 4:30 a.m. on April 18 to April 19. The total CSO from that storm was estimated at 524.9 million gallons.

“We went 22 months without a CSO and now I hope we can go much longer without the next one,” Shafer says. “But when Mother Nature throws these storms at you, it’s something you have to do to protect people’s health and we’re going to do that.”

The storms

Shafer says anywhere from 3 to 4.2 inches of rain fell throughout the area during the first storm. The MMSD service area is a 411-square-mile area with about 5 percent of that combined sewers and the rest sanitary sewers.

The MMSD has a Deep Tunnel system that holds 432 million gallons of combined sewage and then another tunnel — the Northwest Side Deep Tunnel — that holds 89 million gallons from only separated sanitary sewers.

There are also two treatment plants in the district, including the Jones Island Water Reclamation Facility, which can treat 330 mgd and the South Shore Water Reclamation Facility, which can treat 300 mgd.

As the first storm hit the treatment plants began to receive flow and quickly filled to capacity.

“We also had the two tunnels that were starting to fill up,” Shafer says. “We started the combined sewer overflows because our primary goal is to reduce that risk of basement backups.”

Following the storm, the MMSD began to pump the water from the tunnels and treat it at the two treatment plants. Shafer said the storm ended Friday (April 12) and his crews spent Saturday, Sunday and Monday pumping the system and treating the water.

Just as the MMSD had cleared out the tunnels from the first storm — by Tuesday, April 16 — a second rainstorm rolled in and delivered between 2 to 3 inches. Even though the tunnels were clear, the treatment plants were still at capacity from treating the water from the first storm.

Shafer again made the decision to conduct another combined sewer overflow.

“Always err on the side of protecting people’s basements,” Shafer says.

According to Bill Graffin, public information manager for the MMSD, from April 8 to April 18, more than 5 inches of rain fell in the service area, producing more than 35 billion gallons of water.

“Every inch of rain on the district equals 7 billion gallons of water,” Graffin says.

Into the rivers

Once a CSO is started the overflow water is released into three area rivers — the Milwaukee, the Kinnickinnic and the Menomonee.

“We have 150 CSO locations in our district,” Graffin says. “They flow into the rivers and into Lake Michigan. The combined sewer overflow is not like an oil spill or some other major environmental disaster.”

Graffin noted that when there is a sewer overflow, it’s about 95 percent rain or stormwater that is being released into the rivers and ultimately into Lake Michigan.

“The bacteria that is in a sewer overflow does not live long at all once its in Lake Michigan,” Graffin says. The Great Lakes Water Institute, through a study completed in 2011, noted that Lake Michigan is a hostile environment for bacteria because of its cold temperatures.

Hearing from the public

Graffin says he began receiving phone calls the first week of the rainstorms from customers within the district. “I had a lady call the first week of storms in tears, just sobbing and saying ‘please have an overflow, I can’t have another basement backup,’” he says.

Graffin says a vast majority of the calls he gets are either from people with water in their basement or from someone asking for an overflow before they have a basement backup.

“I think people have begun to understand the interplay between rainfall and overflows since we had a huge storm event in July 2010 that caused basement backups in the area because we couldn’t do anything to stop it,” Shafer says. “We had a number of calls from people thanking us for having these last overflows. I have one saved on my voicemail from a lady in Milwaukee who was very heartfelt.”

Shafer still hears from those who say more is needed to stop combined overflows, but there isn’t much more that can be done.

“We’ve got 521 million gallons of total storage right now and if you look at our rainfall over the last two weeks, that’s over a billion gallons,” Shafer says. “We would have had to have at least two or so more tunnel systems to capture that water. That’s a huge investment.”

Avoiding overflows

Even though the MMSD is allowed up to six combined sewer overflows per year by the state and federal government, Shafer prefers not to have any.

Before the first overflow on April 10, the last combined sewer overflow was conducted in June 2011.

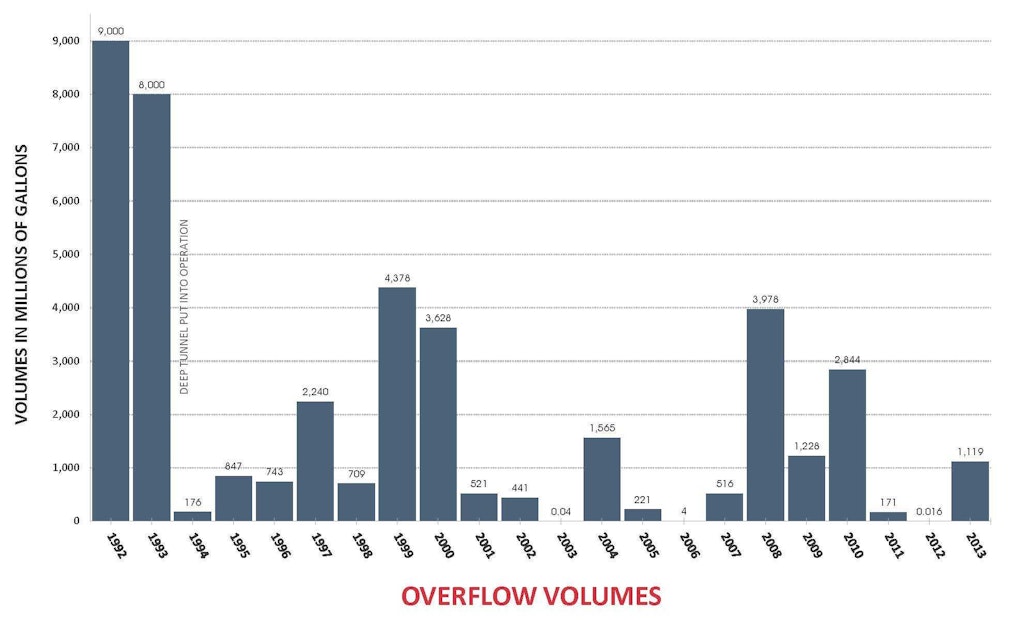

Since 1993 the Deep Tunnel system has captured 98.3 percent of all water that has come to it, according to Shafer. Overflows amount to only 1.5 to 1.7 percent of the water that is captured.

“People don’t understand how much water we actually treat and capture,” Shafer says. “Before the tunnel system, we had 50 to 60 combined sewer overflows per year, now we average 2.5. I don’t know of another combined sewer system in the country that has a better record than this district.”

The MMSD was awarded the U.S. Water Prize from the U.S. Water Alliance in 2012 for protecting water quality.

“I’m very proud of the system,” Shafer says. “I think the Deep Tunnel was a marvelous investment for the region and we’re going to reap the benefits of that system for many years to come.”