In certain parts of the country, road salt is a big contributor to increased salinity in freshwater sources. (Photo by University of Maryland)

Interested in Infrastructure?

Get Infrastructure articles, news and videos right in your inbox! Sign up now.

Infrastructure + Get AlertsA recent study is shedding more light on the scope of a problem that has ramifications for both drinking water quality and the condition of underground infrastructure — increased salinity of freshwater sources.

A National Science Foundation-funded study looked at data over a 50-year period at 232 river and stream monitoring sites across the U.S. The data showed significant increases in both salinization and alkalization.

“We created the term ‘freshwater salinization syndrome’ because we realized that it’s a suite of effects on water quality,” says Sujay Kaushal, a biogeochemist at the University of Maryland and lead author of the study.

Over the 50 years covered by the study, the researchers concluded that 37 percent of the U.S.’s rivers and streams experienced significant increases in salinity. Alkalization, which is influenced by several factors in addition to salinity, increased in 90 percent.

According to Kaushal, most freshwater salinization research has focused on sodium chloride, better known as table salt, which is also the dominant chemical in road de-icers. But salt has a much broader definition, encompassing any combination of positively and negatively charged ions that dissociate in water. Some of the most common positive ions found in salts — including sodium, calcium, magnesium and potassium — can have damaging effects on freshwater at higher concentrations.

“These cocktails of salts can be more toxic than just one salt, as some ions can displace and release other ions from soils and rocks, compounding the problem,” says Kaushal. “Ecotoxicologists are just beginning to understand this.”

The study is the first to simultaneously account for multiple salt ions in freshwater across the United States and southern Canada. The results suggest that salt ions, damaging in their own right, are driving up the alkalinity of freshwater as well.

The causes of increased salt in waterways vary from region to region, Kaushal says.

In the snowy Mid-Atlantic and New England, road salt applied to maintain roadways in winter is a primary culprit. In the heavily agricultural Midwest, fertilizers also make major contributions. In other regions, mining waste and weathering of concrete, rocks and soils releases salts into adjacent waterways.

“This research demonstrates the value of long-term data in identifying potential threats to valuable freshwater resources,” says John Schade, a National Sciences Foundation Long-Term Ecological Research program director. “Without such long-term efforts, widespread and significant degradation of water quality by human activities would remain unknown. Now we can begin to unravel the causes and develop strategies to mitigate potential effects on the environment and public health.”

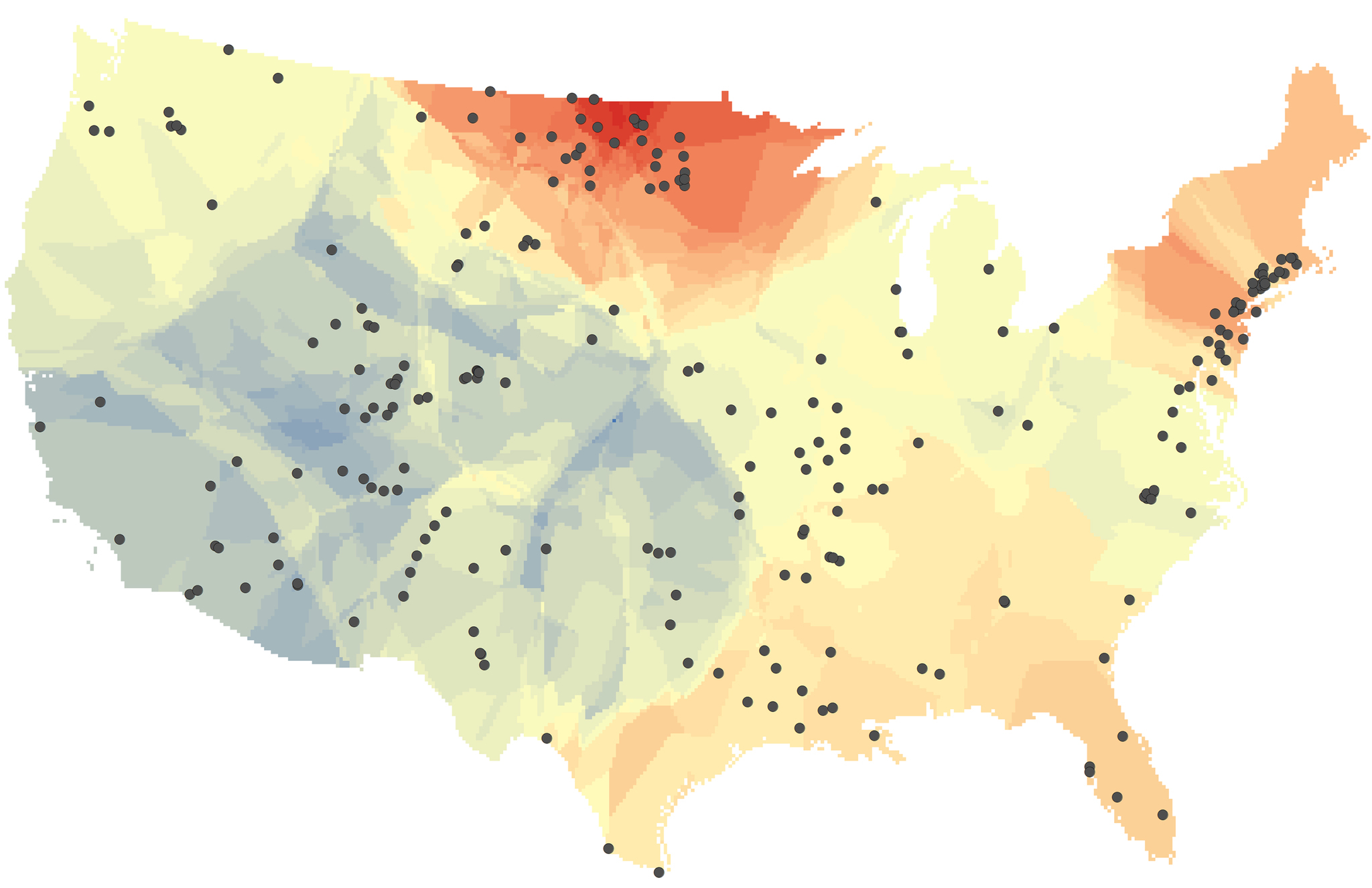

This map shows changes in the salt content of freshwater rivers and streams across the U.S. over the past 50 years. Warmer colors indicate increasing salinity and cooler colors indicate decreasing salinity. The black dots represent the 232 monitoring sites that provided the data. (Image by Chatham University)

Kaushal notes that many strategies for managing salt pollution already exist. Evidence suggests that brines can be more efficient than granulated salt for de-icing roads, yielding the same effect with less overall salt input. Presalting before a major snow event can also improve results.

“Not all salts are created equal in terms of their ability to melt ice at certain temperatures,” Kaushal adds. “Choosing the right salt compounds for the right conditions can help melt snow and ice more efficiently with less salt input, which would go a long way toward solving the problem.”

Kaushal also says that many Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern cities and states have outdated and inefficient salt-spreading equipment that is overdue for an upgrade.

The researchers note similar issues with the application of fertilizers in agricultural settings. In many cases, applying the right amount of fertilizer at the right time in the season can help reduce the overall output of salts into nearby streams and rivers.

And more careful urban development strategies — primarily building farther from waterways and designing better stormwater drainage systems — can help reduce the amount of salt washed away from weathered concrete, the scientists say.

The study co-authors believe there’s also a need to monitor and replace aging water pipes throughout the country that have been affected by corrosion and scaling, or the buildup of mineral deposits and microbial films. Such pipes are particularly vulnerable to saltier, more alkaline water, which can increase the release of toxic metals and other contaminants. Case in point, Flint, Michigan. High chloride levels were partially to blame for the pipe corrosion that caused lead to leach into the water.

“The trends we are seeing show that we need to consider the issue of salt pollution and take it seriously,” Kaushal says. “These factors are something we need to address to provide safe water now and for future generations.”

Source: University of Maryland