Traditional and cutting-edge Internet technologies help the City of Atlanta staff keep residents involved and supportive of improvement initiatives.

Case in point: When the city embarked on its Clean Water Atlanta program, one of the largest infrastructure rehabilitation and improve-ment programs in history, everyone knew that community involvement and acceptance would be vital.

The work, lasting for years, would cause disruption, interrupt services, delay traffic, bring potential rate and tax increases, and have other effects typical of large public construction projects. Since those impacts couldn’t be avoided, the staff planned carefully to get all stakeholders onboard and working with the city to meet its consent decree initiatives.

The solution was to create the Office of Public Participation within the city’s Department of Watershed Management. It began in 1994 as a one-person operation with Marilyn Johnson as director of communications, supported by a few outside consultants. It has since grown into one of the most comprehensive and technically advanced community outreach programs in the United States. By embracing technology, Johnson was able to multiply herself and deliver the city’s message in a cost-effective and broad-reaching way.

The big picture

In 1993 the Bureau of Pollution Control, as part of its phosphorus reduction program, set out to build a wastewater conveyance tunnel between two wastewater reclamation centers on opposite ends of the city. This multi-million- dollar plan was ultimately scraped after extensive public opposition.

That event was the impetus for starting a proactive public participation and community outreach program. It includes a structured process for getting public input before the city moves forward with investment in any specific project plan. Public involvement and public information programs cover a wide range of projects.

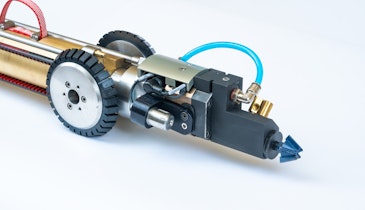

Street-based construction — some 24 contracts per year, typically varying from $5 million to $10 million — require high-level coordination with Neighborhood Com-munity Groups. The overall sewer rehabilitation program incorporates many techniques, including cured-in-place pipe lining, pipe bursting, point repairs, manhole repairs, and open-cut trench replace-ment, all requiring explanation and interpretation about their impacts at the grassroots level.

Activities such as smoke testing and CCTV inspection require grassroots work in communities to facilitate contractor access to properties. In addition, projects must be coordinated with other contract work being performed in the city, including gas and water main replacement, streetscape upgrades, and paving.

The public involvement process typically begins with a series of public meetings where city representatives present the problem and possible solutions to the community. The design engineers take community input into consideration. Often, citizens’ suggestions are implemented when they fit with the budget and engineering constraints.

The meetings are followed by web site postings, media publicity (including television and radio), mailers, and door hangers. Personal contacts are also important, especially in areas with many businesses and office buildings. A large share of the city’s sewer rehabilitation work takes place on easements or private property, and in such cases, personal contact is essential.

The city now repeats the basic process in whole or in part for each new project under the Clean Water Program.

Ever evolving

As the Clean Water Program progressed, so has the level of community outreach. “The program evolved as a more astute public began to seek out information about technical projects proposed for their neighborhoods,” says Johnson. She develops Atlanta’s program from two distinct angles: public involvement and public information.

Public involvement invites residents to participate in every phase of project development, beginning with evaluation of alternative solutions. “If done properly, public involvement affords affected stakeholders the opportunity to voice their concerns and preferences, which are then taken into consideration by technical and political decision makers,” Johnson says.

After the public involvement phase, Johnson and her department provide timely dissemination of information about project activities, especially to residents and businesses that may be directly affected.

“The NIMBY (not in my back yard) mentality will never go away, but people are far more receptive if they feel that they have been given an opportunity to understand and influence what goes on in their back yards,” Johnson says.

Embracing technology

Although Atlanta uses traditional communications like printed billing inserts, direct mail and personal contact, its most powerful and far-reaching communications have used electronic tools, chiefly two Department of Watershed Management web sites: www.clean wateratlanta.org and www.atlanta watershed.org.

The Internet gives Johnson the best means for delivering timely and up-to-date information to Atlanta’s 480,000 residents. The sites feature user-friendly navigation, an easy-to-understand interface, and numerous levels of detail not typically seen on web sites.

The web sites have been crucial to getting an early start on helping ratepayers, elected officials and other stakeholders understand the severity of problems that result from aging sewer and water infrastructure.

In developing the sites, Johnson worked with other departments to determine needs and desired outcomes of the public outreach program. The team determined that one of the most important needs was to provide up-to-the-minute project information, news releases and bulletins so that residents could plan and prepare for projects in their neighborhoods or workplaces.

A unique feature is the traffic advisories section, which provides detailed information on road closures, detours and other events for every project in progress or planned in the immediate future. The site is updated each week using information from each contractor’s two-week look-ahead. The schedules are in Microsoft Excel format and are easily uploaded to the site.

The spreadsheets have a column for the “permit code” and the traffic/detour information. The information is color-coded based on impact to the traffic: green means minimal impact, yellow means lane closures only, red means road closure. If there is a road closure, the contractor enters the detour information.

The site also includes educational videos, project maps and progress reports, all updated regularly. A detailed explanation of the city’s consent decree, its mission and the various facets of the Clean Water Atlanta program are all explained in simple language.

Visitors to either site can get a brief overview or read more technical, detailed documents. Sections like “Our Water and Sewer Systems Today” help residents understand how Atlanta’s drinking water and distribution systems work, whom they serve, their challenges, and the capital improvement plans that address the challenges.

The department recently added the webcast to its communications arsenal. A webcast of a public meeting related to a major sewer rehabilitation project in a very dense business district was well attended. A public webcast of a water conservation workshop was also just released. This was done in response to North Georgia’s Level 4 drought conditions.

Project success

Since the Office of Public Participation (now Communications & Public Outreach) started, not one project has been delayed or abandoned due to public opposition, city staff members say. “Despite the enormity of the Clean Water Atlanta water and sewer improvements, the number of complaints and problems that escalate to the desk of the mayor or a city council member is relatively minute because of our communications and public involvement programs,” says Johnson.

Johnson and the Department of Watershed Management constantly find new ways to reach audiences through new technology. Virtual public meetings are among technologies now being considered.

All this communication paved the way for public and political support for multiple rate increases and unprecedented municipal sales taxes that were needed to fund the city’s projects. Johnson observes, “Not every government requires a program as extensive as Atlanta’s, but everyone can benefit from positive public exposure.”