The U.S. Department of Justice Department has penalized more than 50 city and county wastewater systems around the country in the past decade for violations of the U.S. EPA’s 1994 combined sewer overflow (CSO) rules.

Now, Congress has proposed a bill that would toughen enforcement with requirements for monitoring and community notification of CSOs and sanitary sewer overflows (SSOs).

The Raw Sewage Overflow Community Right-to-Know Act (H.R. 2452/S. 2080), with bi-partisan support, would trump and expand the 1994 CSO policy, which often leaves notification and monitoring requirements to the states, whose implementation regimes differ markedly. Rep. Timothy Bishop (D-N.Y.) is the House sponsor of the bill, and Sen. Frank Lautenberg (D-N.J.) is the Senate sponsor.

On the same plane

At present, National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits allow CSOs but do not authorize SSOs. So the EPA has had a much more informal policy toward notification and monitoring of SSOs. The Right-to-Know bill would put CSOs and SSOs on the same regulatory plane, expand the notification requirements and, by establishing a federal requirement, force all states to meet minimum standards on notification and monitoring.

A 2007 report on notification laws in 11 states by American Rivers, the environmental group leading the charge on the Right-to-Know bill, found that only Maryland had a strong program to protect public health against sewage overflows into rivers and other waters.

“Most states reviewed had either no public notification require-ments for sewage spills or selective or sporadic notification,” says Katherine Baer, who directs the healthy waters campaign at Ameri-can Rivers. She agrees, however, that some local communities around the country do a very good job on notification.

But what worries sewer system officials is that the monitoring provision in the Right-to-Know bill could force all NPDES-permitted wastewater systems to install wired or wireless electronic devices at the point of all CSOs, and also at sanitary sewer overflow (SSO) points, such as manhole covers.

Counting costs

In terms of monitoring require-ments, the bill states that sewer utilities “must institute and utilize a methodology, technology, or management program that will alert the owner or operator to the occurrence of a sewer overflow in a timely manner …”

CSO and SSO monitoring systems are not cheap. Kevin Shafer, executive director of the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District, said the agency spent $50 million over the past five years to upgrade its monitoring system so that it can provide immediate notification of SSOs and CSOs, which is what the Right-to-Know bill would require.

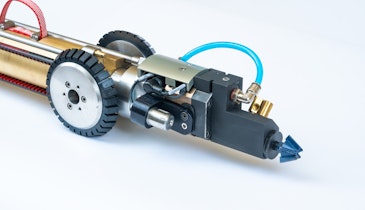

Jeff Graham, president of Hydromax USA, a firm in Louisville, Ky., that provides data collection for condition assessment in buried water and wastewater facilities, says that to install a wireless notification system for SSOs, a community would pay about $3,500 per manhole cover.

SSO notification is trickier than CSO notification, because a sewer system owner is never quite sure where an SSO will occur. That means a monitoring system must cover a fairly large number of possible overflow sites.

With a CSO, there are designated points where an overflow would enter a river or stream. A CSO monitoring system might cost $6,500 per CSO location. In both cases, there are also costs for monthly visual site checks of the system, and other maintenance.

Action expected

Senior Democrats in the House support the Bishop bill, including Rep. James Oberstar (D-Minn.), chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, which held a hearing Oct. 16, the first step in moving a bill forward.

“This well-thought-out legislation would be a welcome addition to federal efforts in protecting public health as well as the natural environment,” Oberstar said. He noted that Duluth, Minn., had just experienced numerous sewer overflows after massive rainstorms in the Lake Superior basin. Jim Berard, spokesman for the Oberstar committee, which has jurisdiction for the bill, said action was likely in early 2008.

The Bishop/Lautenberg bill would expand CSO notification beyond the current EPA policy. Wastewater utilities get explicit permission for CSOs in their NPDES permits, which are issued by the EPA or the state. Those CSOs are subject to a public notification provision included in the EPA’s 1994 CSO policy.

That policy says the public must receive adequate notification of CSO occurrences and impacts. But systems can do that in a variety of ways, including posting of affected areas, posting of selected public places, and posting of CSO outfalls.

The Right-to-Know bill mandates public notification within 24 hours, as well as contacting of local public health agencies, and the sending of a report to the state or EPA within five days providing detailed information, such as the magnitude, duration, and suspected cause, and steps taken or planned to reduce, eliminate, and prevent recurrence. The bill does not define “public notification.”

Bob Matthews, co-chair of the Water Environment Federation wet weather task force, says California adopted a state collection management plan in 2006 that includes a good description of public notification, which a federal law might want to echo.

Taking action

Of course, even without a federal law on CSO and SSO notification and monitoring, the Justice Department, with the EPA, has been acting against many NPDES-permitted cities and counties over the past decade. They include Mobile and Jefferson County (Birmingham), Ala.; Atlanta, Ga.; Knoxville, Tenn.; Miami, Fla.; New Orleans, La.; Toledo, Ohio; Hamilton County (Cincinnati), Ohio; Baltimore, Md.; Los Angeles, Calif.; and Louisville, Ky.

The department hit Sanitation District No. 1 of Northern Kentucky with a consent decree in October 2005 that included a requirement for CSO and SSO monitoring. Mike Apgar, director of strategic initiatives for the district, says the wastewater system uses modeling as its method of monitoring.

There are about 100 CSOs in the district, and when a heavy rain falls, the district assumes there will be events and notifies the Ohio River Authority. Neither the CSO/SSO notification nor the monitoring that Sanitation District No. 1 uses would appear to pass muster under the Right-to-Know bill. Apgar said the cost would be “astronomical” if the district had to install wired and wireless monitors at all CSO and potential SSO points.