It isn’t always easy to manage and maintain an older water distribution system in a historic city like Wilmington, Del. Lately, the one constant has been change.

“Change is our biggest challenge,” admits Lawrence Carson, city engineer. Changes Carson has championed, in the forms of new data collection technology, rehabilitation techniques and GIS mapping, are helping this bustling city improve water quality and maintain its vital water distribution system in a highly efficient and cost-effective manner.

Priority One: Quality

Situated in the northernmost part of Delaware, Wilmington (population 72,000) is one of the original colonial cities of America. Its water distribution network has some sections that date back to the early 1800s. The average size of the city’s water mains is 8 inches, and the median age is 75 years.

To deal with its aging infrastructure, Wilmington works diligently to set priorities for capital improvement programs as well as day-to-day operations. Recent regulatory changes have caused the city to focus on water distribution network integrity, even to the point where water leaves the city system and enters homes and businesses. Several initiatives and projects aim at improving water quality, complying with federal standards, and improving customer service.

Wilmington is in the final year of a four-year contract with Wachs Utility Services to locate, exercise, assess and document every valve within the system’s 400 miles of water mains. At the start of the project, the city believed there were 10,000 valves in the system. That number is now pegged at about 9,700, including fire hydrant guard valves.

Comprehensive data

Wachs Utility Services crews are charged with fully exercising the valves, gathering GPS coordinate data, and returning detailed reports of almost 60 parameters. All of this data is then uploaded and integrated into the city’s ESRI-based geographic information system (GIS). Key value parameters include:

• Valve size

• Size of the water main served by the valve

• Opening direction (right or left)

• Age of the main

• Location (X and Y coordinates)

• Number of turns expected and number actually observed

• Depth of the valve nut

• Condition of the valve box and valve box cover

Technicians perform exercising and data collection on a flexible schedule. “We did have some rough spots where every valve we turned seemed to have a problem,” Carson says. “So we would move the Wachs team to another location, send our valve maintenance crew in to address the valves that were problematic, and then bring the Wachs team back at a later date. It served us well, because you never know what you’re going to find when you start a project like this.”

The city also entered into a valve replacement contract to address valves found to be broken, deficient, or impossible to exercise. Carson and his team are seeing the benefits already. Besides helping the department stay ahead of the curve and prevent valve failures, the program is valuable in dealing with emergencies.

Quick resolution

Case in point: During street improvements on one major thoroughfare, workers struck a 20-inch valve. Water from the leak shot 30 to 40 feet into the air. “For those of us who work in distribution systems, that’s the beginning of a very, very bad day,” Carson says. “It takes a lot to get a shutdown to isolate the leak so you can get it fixed.”

Before the city had extensive data on its valves, the water department often struggled with shutdowns. For every valve that didn’t work, the crew had to fall back two or three more valves. Each fallback means more customers were shut down and inconvenienced. After the repair, crews had to return all the valves to their correct positions — which can be difficult. A typical 8-inch valve takes 27 turns to shut down — a tiring, labor intensive task.

The data collected by Wachs crews helped city personnel execute the shutdown easily. “We actually got a perfect shutdown on this 20-inch main,” says Carson, “During the shutdown, we only knocked two people out of water. In one case, only the fire service was cut off. Only one business was inconvenienced in a zone that was a half a mile long by three city blocks wide.”

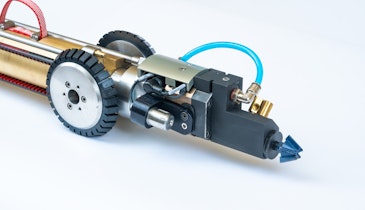

Once the initial Wachs Utility Services contract is completed, Wilmington plans to purchase a Trailer Mount Exerciser/Swivel Vac unit from E. H. Wachs Co. so that in-house staff can perform some of the ongoing valve exercising.

“I think there may always be a place for a contract like this, simply because we never seem to have as many people as we need to do the job that we are pressed with doing,” says Carson. “If we can get someone in who can focus on doing this work, that’s a plus.”

Trenchless rehabilitation

Improvements to the distribution system also include rehabilitation. Some areas in the network generate complaints about poor water quality, low pressure, low flow or low fire flow capacity. To address this, the city works with Hatch Mott McDonald, a local engineering firm, to track all issues over time.

The firm will help the city improve its approach to capital improvements, set repair priorities, and get the most value for improvement dollars. The intent is to develop projects that address as many complaints as possible with the budget available.

Cleaning and relining is one program that delivers strong return on investment. “If the mains are structurally sound, we believe we can do a mortar lining that’s going to rehabilitate the line for 50 cents on the dollar, versus what it would take to replace the line,” Carson says.

Although the city still replaces lines when required, cleaning and relining is the preferred choice by a 3-to-1 ratio for work planned in the near future. During the process, a cleaning pig first removes tuberculation from the cast-iron mains. A viscous cement mortar is then applied while a second pig smoothes the material, creating a clean, like-new surface.

Along with main rehabilitation, Wilmington often goes a step further, adding replacement service laterals, eliminating lead or galvanized service connections. This supports the city’s efforts to improve water quality and stay ahead of the regulatory curve. “We’re doing this as a service to our customers, and to limit our exposure with lead piping issues,” Carson says.

When water main projects are planned, the city sometimes resurfaces the roadway at the same time, creating efficiencies, saving costs, and pleasing residents.

Going paperless

Perhaps the biggest change in the city is migration into the electronic world. Carson and his team are on an aggressive program to convert what was once a paper-and-pencil office into a state-of-the-art electronic information center. Although it took time and effort to win over the staff, the department now sees the benefits of having up-to-date information available at the click of a mouse.

The city is creating an Intranet using an IMS server that enables staff to access aerial photographs, topography lines, street centerlines, traffic signals, valves, manholes, the sewer collection system, the water distribution system, and all roadways, and search by street names.

“Just about any infrastructure that you can think of, you can get to via the IMS,” Carson says. “Beyond that, we can superimpose the water distribution mylars that have been scanned, so we can actually go and find the detail of what’s in any given street. We’re moving toward a situation where we can do the same with the sewer mylars and any of the other scanned documents that we have in our possession.”

Another benefit of the GIS is how it will provide the city with “institutional memory,” he adds. Over the past several years, the city has downsized its staff and experienced attrition. When that happened, some programs were abandoned and knowledge about the city’s infrastructure and systems was lost.

“My hope as manager of the GIS program is that instead of having programs fall apart at troubling times like that, maybe the GIS can provide the institutional memory and those programs can continue,” says Carson.

In addition to its GIS, the city recently rolled out the Service Request component of the CityWorks Asset Management system from Azteca Systems. Plans call for activation of the Work Order component by the end of the current fiscal year, and the addition of the Asset Management module by the end of the following year.

Change is good

The City of Wilmington is committed to changing its thinking, methods and technology when necessary to make its water distribution system what it needs to be. Carson encourages other municipalities and water agencies to embrace technology, especially data collection about their assets and deployment of GIS.

“I can see the ability to leverage our data in ways that were probably unthinkable as little as a decade ago,” he says. “There are things we have on the drawing board that are going to really help us look like the professional organization that we truly are.”