Part way into an ambitious project to end combined sewer overflows (CSOs), the City of Lansing decided to make it even more ambitious — but also more efficient. The plan: to coordinate the CSO project with other utility work throughout the city, and so reduce disruption from major construction projects.

The city’s Public Service Department has been following through on the coordination plan since the late 1990s, working with the independently run Lansing Board of Water & Light (LBWL) and other utilities whose work might interact with the CSO project. The result has paid off, says city public service director Chad Gamble.

Where his department and the board once clashed over projects that ended up at cross-purposes, they now work together from the moment the first plans are drawn up. “It truly is a project team that comes together,” Gamble says.

The big cleanup

Lansing, Michigan’s capital, launched its CSO project in the early 1990s. “It’s a 30-year construction project meant to separate the city’s combined sewers and thus put us into compliance with the Michigan Department of Environ-mental Quality,” Gamble says.

Stormwater, snow melt and surface runoff water flowing into catch basins in the city’s combined sanitary and storm sewer system had resulted in combined sewer overflows of as much as 1.65 billion gallons per year into the Red Cedar River or the Grand River.

In the 1980s the city separated 4,150 acres of combined sewers, but by the early 1990s there remained another 7,000 acres. Under an agreement with the Michigan DEQ, Lansing in 1992 drew up a new set of plans to separate those sewers with a deadline of 2019. The project budget was set at $176 million in 1992 dollars; Gamble says the cost when all is finished is likely to reach $500 million.

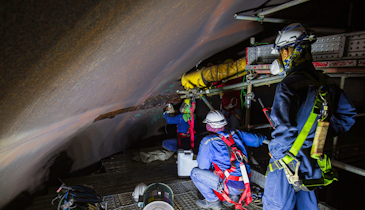

The CSO project entails installing new sanitary sewer lines parallel to the existing combined lines. Once in place, the new sewer mains are switched into service, while the former combined sewer reverts to use strictly for stormwater. As of January 2008, 3,825 of 7,167 acres of combined sewers had been separated.

Gamble, who joined the city in 1996, says that as the CSO project unfolded, it soon became clear there were problems. “There was a lot of friction between the LBWL and the city,” he says. “There wasn’t a lot of communication.”

For instance, sometimes a new sewer line would be installed, and then, after repairs were completed, another utility would do work in the same area. “It could be a gas main, it could be water, and it happened frequently,” Gamble says. “They’d damage the infrastructure that was just put in there because it was brand spanking new and wasn’t on their as-builts.

“We had problems with people tripping over themselves. Traffic control was very confusing, because you had two contractors in there with two separate contracts. There was a lot of finger-pointing going on.”

John Matuszak, senior engineer at the LBWL, recalls, “The board was in a reactive mode in the early days of the program. We weren’t terribly successful in staying ahead of the contractor or coordinating our work with the CSO contractor’s work.”

Teaming up

The two agencies made some simple efforts to work more closely, mainly by enabling the LBWL to piggy-back on the city’s contractor selection process. “We would issue a contract, and we’d let the board know about it, albeit real late in the game,” Gamble recalls.

Once the city had selected its contractor (typically the lowest qualified bidder), the LBWL usually opted for the same contractor. But there was a problem: “Those prices were not competitively bid,” Gamble says.

Trying to cut a deal with just one contractor who had already been chosen “wasn’t really in the best interest of our public,” adds Kellee Christensen, who was supervisor of customer projects at the LBWL at the time. “It wasn’t really a formula for good pricing.”

Matuszak doesn’t believe the LBWL was ever charged unfairly, but given that the contractor was already chosen for the city portion of a project, if the water agency wanted to come in and work in the area as well, it was essentially stuck with the same contractor and didn’t have much flexibility in negotiating terms.

The problems reached a head when the city took the separation project to a neighborhood near the state capitol. “We had been working with the businesses to make sure access would be maintained at all times during the project,” Gamble says. “We were getting into the summer months, and construction was going hot and heavy, and all of a sudden, I get a phone call from a business owner who said, ‘What the heck’s going on here? You said the street wasn’t going to be closed, and now it’s closed and people can’t get to my business.’”

When municipal construction ties up a street, taxpayers and motorists don’t stop to calculate whether the culprit is the city or some other agency, Gamble points out. “From their point of view, it’s our job, public service’s job, to coordinate it. And why shouldn’t it be?”

Gamble, by this time assistant city engineer in charge of CSO construction, and Christensen at the LBWL, knew things had to change. “We just said, ‘Let’s try to find a way to work better,’” Gamble recalls. The result of several months’ of discussion was a memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the LBWL and the city, outlining how the agencies would work together as the rest of the CSO project unfolded.

Incentives to cooperate

The CSO project has encompassed 20 individual projects so far, and many more are planned. Each project has a five-year life span: Two years of planning, two years of execution, and a year to wrap up. Under the MOU, instead of waiting until the last minute to reach out to the LBWL or other agencies, Public Service brings in other affected agencies on the ground floor.

“That two-year time frame is when we send out maps and remind our friends at the other utility companies that we’ll be in the area,” Gamble explains. Officials at the LBWL or other utilities are encouraged to review their systems and identify necessary upgrades to the section that is slated for renovation. Draft plans are shared among all the involved agencies, so that any potential conflicts can be quickly resolved.

Christensen says that the LBWL has taken the opportunity to improve, upgrade and replace aging infrastructure, following its Lansing Master Plan.

Lansing has also put in some incentives to get other utilities to coordinate projects. Working together early allows all the agencies to coordinate bidding, getting the best possible price for the work. It also makes the overall projects bigger. “It’s given the board a savings from economies of scale,” says Matuszak. “There’s more competition, and I think we get better prices.”

Coordination also helps the LBWL “better leverage resources,” says Christensen, who is now the LBWL manager of customer projects and development. “With all the work the city was doing, we were not staffed to handle that type of influx.”

But cooperation has sticks as well as carrots. “We’ve tried to make it a little bit more painful for utilities who do not work with us,” says Gamble. For instance, road cut fees escalate sharply based on how new a street is. Outside utilities are learning that it’s a lot cheaper to work with the city rather than just go their own way.

And while the only formal agreement is with the LBWL, the city still works with all other utilities as well. For example, early in the planning process, the city encourages natural gas suppliers to get involved so that they can plan for new gas mains that mesh with the plans for new sewer lines.

Making it work

The more complex projects helped bring all potentially involved utilities up to speed in codifying uniform technical specifications. That, too, improves the bidding climate because specs are now clearer to potential contractors.

Because so many more people, project details and agencies are involved now, planning becomes even more important. “This large of a project deals with a lot of paper,” says Gamble. “We’ve done some things in the last couple of years which have cut down on the paper shuffling.”

Digital technology helps. To ensure proper contractor cost estimates and payments, the parties use forms created in Adobe Acrobat that can be e-mailed to the project signatories. “They electronically sign that document, as opposed to hand carrying that over and having problems getting things done in a timely fashion,” Gamble says.

An internal project Web site now offers a central repository for all estimates, plan sets and work-change directives. “If people have questions about things, we can give them access rights to this,” Gamble says. That includes any other agencies that may be involved with a particular project.

Along the way the city regularly reviews each year’s work on the CSO project. “We look at the things we’re doing well, and continue doing those, and look at the things where we dropped the ball and communications failed,” Gamble says. “We look inwards to see how we can continually improve our processes.”

Keeping the focus

Willingness to re-examine old ideas and practices has led to other changes. One of them is in the material specifications for items such as sewer lines. “We have been historically only a clay tile community,” Gamble says. “We had not allowed PVC piping to be installed for sanitary mains at all.”

That changed two years ago, when the city looked again at PVC’s track record and decided it had proven competitive with clay. Now, PVC is the material of choice for much of the sewer replacement work.

Bigger projects and more people all add up to more challenges, but they also make for better results. Attitude is key. “We have a great team of individuals who understand the end game, and that’s making sure we’re doing the best thing for our customers,” Gamble says.

“Sometimes people lose that focus of why we’re there, why we have to go to meeting upon meeting and coordinate things and try to poke holes in things,” Gamble says. “We do it just to make sure that when we get into construction we have a good communication line, an excellent set of construction documents, and an excellent set of inspectors who know our specifications, and who have gone through our qualification process.”

The payoff, he concludes, isn’t just in the results. It’s found in what doesn’t happen. “These projects are very, very difficult to put together,” he says. “Sometimes the planning stages can get arduous, because of all the people that need to see it. But the pains in putting together a sound project will be reaped by not being in front of a TV news camera and explaining something that didn’t go right or a road that you had to get back in and re-excavate. This is a much better atmosphere.”