When five inches of rainfall in a two-hour period revealed that its system’s stream conflicts were more significant than originally thought, Johnson County Wastewater (JCW) decided to take a proactive approach to maintaining its sanitary sewer conveyance system.

Its efforts have gained national recognition for forward-thinking system management and maintenance that uses asset-management information, multi-tier physical pipeline inspection, and analysis tools such as geomorphology, hydrology and plant taxonomy to develop the most effective and sustainable means of rehabilitation.

By systematically approaching infrastructure that crosses streams, the county has reduced its long-term maintenance and operations costs, while creating a more sustainable system that can coexist with the environment.

Risks revealed

Located in eastern Kansas, JCW serves more than 130,000 customers and is responsible for maintaining and operating 2,100 miles of sewer lines. The system contains an estimated 5,300 stream crossings, which are at-risk assets because of their exposure to stream-forming processes that are constantly changing the waterways’ natural meandering pattern.

The true risk of these assets was revealed in October 1998 when rainfall over a seven-day period saturated the ground and caused significant collection system damage at several stream crossings. Then four more inches fell on top within just one hour and 15 minutes, flooding many local streams with torrential flows. During the cleanup, it became obvious that stream conflicts were a more serious threat to the overall health of the system than previously imagined. System capacity and water quality can be jeopardized by damage to sewers at these crossings.

Needing to know exactly where the system stood, JCW began what would become a routine program of stream-crossing inspections. “We divided up into teams, took on different watersheds within our jurisdiction and physically visited every crossing during the winter months,” says Aaron Witt, engineering manager for JCW. “We walked along all of our streams with our maps and searched out any pipes with any type of potential problem. This step is now the initial phase of each of our scheduled surveillances.”

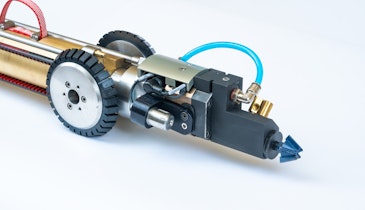

The teams note specific measurements such as pipe size and condition, and take photographs. Sewers that are buried or located on stable streams typically do not warrant further assessment. But if a line is exposed, a crew completes an additional evaluation of its condition, using CCTV inspection. An evaluation of existing stream reach condition is conducted as well.

Regular inspections

Since 2003, the utility has taken a proactive approach, inspecting all 5,300 stream crossings every two years. As part of an asset management program, the inspection data is compiled in the utility’s asset management program, GBA Master Series. It is then analyzed, and all assets are assigned a condition rating and risk level.

Damage caused by erosion and natural water body movements are typically gradual, but can be accelerated during major wet-weather events. Through its inspections, JCW noted that over time, some streams may move up or down, or from side to side.

This shift is most often caused by stream straightening or channelization, floodplain encroachments, and increased impervious areas in the watershed, all common in the thriving Johnson County area.

“We found that most of the significant stream changes have occurred in high-growth areas where, when the sewers were first laid, the streams were very small, more like little country creeks,” says Witt. “As the population grew and buildings went up, the amount of hard, impervious surface grew, too. All the runoff from the streets and the roofs began hitting those small streams, creating a lot more flow. The streams had to find a way to dissipate that energy, so they looked for ways to widen and cut through.”

Working with nature

Typically, JCW repaired the stream-crossing lines using traditional techniques such as riprap or extension of concrete encasements to divert flows. But while calculations for the design of armoring methods allow for a rock or barrier size that cannot be dislodged during a storm event, these armoring techniques can actually block a stream’s natural movement and changes. In some cases, armoring had the potential to create more destabilization and increase the risk to the sewer at the repair site, as well as upstream and downstream.

To avoid creating problems from installation of solutions that might not be the best fit in the long run, JCW brought GBA Architects and Engineers onboard to assist in developing a stream characterization approach. This would help JCW understand the area’s current watersheds and how growth and development might change them.

In addition to watershed analysis, GBA provided localized stream reach surveys, because site-specific influences play an important role in determining the most appropriate repair approach for long-term sustainability. “People often underestimate the power of water and its erosive forces,” says Paul D. Miller, senior engineer and stream specialist with GBA. “You have to respect it and try to understand how it moves across your landscape in order to come up with solutions that work with nature’s flow and not against it.” Under these principles, the design for a repair takes into account the dynamics of the environment and the stream’s stability rating: dimensions, sediment load, pattern and profile.

Scientific tools

This approach helps JWC develop more sustainable solutions that will need less maintenance and reduce the potential for infiltration and inflow issues in the future. The approach can use scientific specialties such as stream geomorphology, which analyzes water and earth forces that form stream channels, floodplains, terraces, drain patterns and sediment movement. The tool kit also includes hydrology studies and riparian plant taxonomy to help JCW develop greener solutions.

JCW identified more than 30 crossings that required repair, either by JCW staff or through design and construction contracts. Whenever possible, the utility does the repairs in-house. Rehabilitation methods have evolved from traditional armoring to include:

• Blended material armoring with a layered design

• Installation of specialized stream grade control revetments over sewers.

• Realignment of segments of sewers to mitigate natural channel movement.

• Natural plantings.

“When we are dealing with an exposed line in a degraded stream, we take into account the water body’s present condition, the watershed characteristics and what the future trend of that stream will be — how it will want to stabilize itself,” says Miller. “Only when we gain knowledge of a stream’s tendencies can we design a long-term solution that will fit with nature and protect the asset.”

Acting natural

One of the most common designs that Miller and his Stream Team have devised is a twist on traditional armoring. In the case of pipelines or other fixed utilities, traditional rock armoring doesn’t provide a long-term stable solution for the stream, especially during a storm event, as the water’s flow will keep shearing off the rock, creating a maintenance issue.

To combat this, the design team devised a layering technique to create a structure that mimics the natural streambed. At the bottom, large armoring rock is used, but unlike standard riprap, it isn’t uniform in size. The larger boulders are specifically selected for their shape and size based upon the stream stability parameters established during the review process.

Then, a blend of other materials including rocks of varying gradations, pebbles and fine sand is layered to the desired height around and on top of the foundation. “Instead of a design that has numerous voids that are typical of traditional armoring, we layer and blend materials to create an area where there is soil and fines in between,” Miller says. “The natural system can take over and stabilize the entire area.”

Vegetation-based solutions are highly desirable but are best suited for areas with a relatively healthy, continuous and unobstructed rip-arian corridor. Although an excellent solution that also offers environmental beautification, some plantings — like large trees or shrubs — cannot be placed too close to wastewater structures, as that could lead to root intrusion. This limits the number of projects where a vegetation-based solution can be used.

“Our approach has truly changed from the way it was in the past,” Witt says. “Before, we just tried to pack everything in hard so it protected us. Now we try to understand the stream. Plus, it’s not very pretty when you use a high-degree, hard-armor solution in a natural setting. This approach has allowed us to look at other options, such as natural stabilization of stream banks or crossings using erosion control mats and native plantings that are more visually pleasing and just as effective, if not more so.”

These new approaches will also offer Johnson County a longer lifecycle and return on investment for its rehabilitation projects. It also helps prevent a shifting of one asset’s issues downsteam to another asset. “What can happen quite often is that when you try to armor one stream bank to protect an exposed pipe or manhole, the stream will adjust to the changes imposed by the new barrier you’ve installed,” says Miller. “Then it will transfer the problem you just experienced to another location, possibly affecting other infrastructure either upstream or downstream within a relatively short time.”

GBA has observed that clients who design solutions using the stream morphology approach create rehabilitations that last longer with less maintenance costs and with lower impact on property owners.

Always vigilant

The utility conducts ongoing observation of repaired stream crossings and rehabilitation measures during its regular inspections. JCW has also launched an asset management program to lower the risk of system failures throughout its sewer system — not just at stream crossings.

By surveying the entire system on a consistent basis, JCW can be confident that nothing has been overlooked. “It is important to get out and be proactive and look in parts of your system that you don’t always get to during regular routine maintenance,” Witt says. “That includes undeveloped areas — those places where we may never get a call and will only discover a problem after it becomes serious.”

With this attitude and methodology, JCW has minimized damage and realized cost savings. But for Witt, the main objectives have always been the same: Protect the system, protect the customers, and protect the environment. That’s an approach that could serve as an excellent model for wastewater utilities around the nation.