In a city as “flat as a pancake,” 6,250 miles of sanitary sewer is a recipe for trouble. The main ingredient in that recipe is grease, says Bill Goloby, a project manager in the City of Houston (Texas) Wastewater Operations Branch.

“Grease causes stoppages, and stoppages cause sanitary sewer overflows,” he explains. “And now that SSOs are being regulated, cities all over the country are starting to look at grease buildup and ways to reduce it. We’re looking at it harder than most.”

Houston concentrated on weather-related SSOs because that was a reasonable place to start, according to supervising engineer Steven Gee, P.E. “We started with the idea that our problems were weather-related, but we noticed that the quality of water wasn’t substantially affected by wet-weather overflows because they are diluted to the point that they’re not notice-able,” Gee adds. “Dry-weather SSOs were actually a bigger problem because of the higher concentration of pollutants.”

Concentrating on dry-weather SSOs led the city to focus on grease, because crews routinely reported that grease and rags caused the majority of stoppages.

Grease is a bigger problem, or rather a bigger percentage of the overall SSO problem in Houston. That's because the majority of the sanitary sewer lines are concrete and are laid very flat. It’s also because there is relatively little root intrusion.

To reduce grease buildup and blockages, Houston has been replacing lines with an aggressive pipe bursting program. In addition, it has put significant effort into a public outreach campaign. As a result, SSOs per mile of line have been reduced considerably in recent years — except for problems caused by Hurricane Ike in 2008.

To the streets

The grease-control initiatives first focused on dining establishments. “When the rules changed and cities all over the nation had to do more about SSOs, restaurants were an obvious place to start,” says Goloby. “We made good progress there with inspections and enforce-ment, but a lot of stoppages were still being caused by residents.” After the restaurant association pointed out the residential issue, Goloby’s branch decided to make residences a priority.”

In a city the size of Houston, a public outreach program has to be quite large to make an impression, and it was important to make the most of the initial $275,000 capital investment. The wastewater operations branch started in July 2005 with an initial printing of one million “Corral the Grease” pamphlets.

To brand the program, Houston consistently uses “Corral the Grease” as a metaphor, encouraging residents to capture grease in containers and dispose of it as solid waste, rather than putting it down drains. To accommodate the local population, the pamphlets are bilingual. Illustrated with graphic photos, they explain the effects of fats, oils and grease on lines, list acceptable containers for grease, and describe the relationship between SSOs and water quality in local bayous and waterways.

“Luckily for us, the brochure was sized — by accident, not planning — to meet the water division’s guidelines, so we were able to include it with one of their mailings,” Goloby says. That mailing, in September 2005, distributed 430,000 copies. In 2006, another 460,000 were mailed directly to apartment complex residents, and the rest were distributed in other ways. The brochure distribution is considered effective, and large reprintings have since been ordered.

Bang for the buck

The city targeted apartment complexes for two reasons. First, apartments concentrate grease-producing kitchens and bathrooms. Second, and less obvious, “A lot of people in apartment complexes don’t get a water bill and don’t care much about wastewater disposal, because they don’t know about the consequences of blockages,” Gee says. “But now, apartment owners and managers are getting involved.”

By working with managers, making presentations to tenants, and distributing fat trapper kits, the department has seen measurable reduction in line blockages near apartment buildings. Other efforts aimed at apartments include newsletters, Web-based information, and special line-cleaning initiatives.

The fat trapper kits consist of a plastic container with custom logo, heatproof bags that fit the container, a universal lid for cans, a “Corral the Grease” pamphlet, and a refriger-ator magnet. The city initially distributed 15,000 kits, which were effective but costly. “They required assembly and hand distribution,” Gee says. “Basically, the logistics were hard, and the city council balked at the expense of the containers. Now we just go with lids.”

The universal lids, which also have the “Corral the Grease” logo, fit most cans and turn them into a safe, heatproof storage device for cooking grease. After the grease cools, it can be disposed of in ordinary trash containers as solid waste.

Special efforts also have been made in particular residential neighborhoods. “Certain ethnic cuisines tend to use or produce more grease,” Gee says. “Some of these neighborhoods are in areas with older sewer lines, which tend to block more easily.” Bilingual mailings to these neighborhoods have been very effective.

Bringing it to life

About $5,000 of the original outreach budget went toward design and creation of a mascot costume. To fit the “Corral the Grease” concept, the mascot is a clean, cheerful planet Earth with a cowboy hat and a lasso.

“The costume is a great draw for kids at the events we go to,” says Goloby. “Kids don’t pay much attention to the brochures, but the mascot gets them to listen. We want to reach the kids because they have an impact on parents, and because they’re the future.”

To enhance the costume, the city held a naming contest, and the winning entry was “Greasebuster.” To go along with that, students in a high school for the arts produced a “Greasebuster” theme song, which is played when the mascot appears before certain groups.

Goloby says a news spot that ran on a local TV station was “the best thing TV has ever done for us.” Billboards may be part of the mix in the future, and the department also hosts booths at fairs and other public events.

Saving the pipes

Of course, public information alone won’t do the job. Therefore, the city runs an aggressive maintenance program.

“In my experience, concrete pipe is always an issue, especially here,” says Gee, “Temperatures in Houston are as high as anywhere, and so we get more sulfide deterioration. We don’t have any slope. Our soils are typically high-plasticity clay and expansive, so we have a lot of problems due to our local topography.

“For example,” Gee adds, “when there’s no grade and a low flow, many of our smaller sewers rarely reach self-cleaning velocity, which means we have a lot of debris settling. I also don’t have a feel for how inspections were being done when much of the concrete pipe was being laid. We have a lot of sag issues, which also causes settling and blockages.”

Another consequence of flatness is the high number of pump stations; Houston has more than 440.

“I know we have more problems than other cities,” Gee says. “When I mention our stoppage issues to other city managers, they’re shocked.”

Because concrete pipe leads to so many problems, replacement with HDPE is a high priority. Pipe bursting is the preferred technology. “My feeling is that Houston was instrumental in moving pipe bursting from the gas industry to the sewer industry,” says Gee. “I think that happened when sewers stopped being a dirty word and became an environmental issue.”

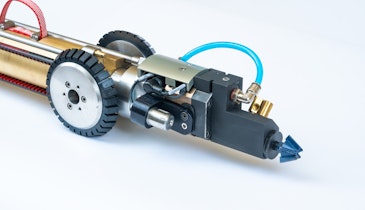

Private sewer service companies perform all sliplining and pipe bursting of city sanitary sewers under annual or multi-year contracts. Some of the systems that have been used to pipe burst sewers are Grundocrack (pneumatic) and Grundoburst (hydraulic/static) systems from TT Technologies Inc., and systems from HammerHead.

The city has used these systems to burst pipes made of reinforced and unreinforced concrete, clay, cast iron and other materials. The program now includes bursting of some 65,000 feet of 6- to 18-inch sewers each month.

Keeping it clean

Along with rehabilitating pipe, Houston cleans significant footage annually. “We are committed by an agreement with the state to clean 2 million feet of sanitary sewers annually, but we’re exceeding that,” says Gee. “In recent years, we’ve been cleaning 3.5 to 4 million feet annually.” That amount of cleaning requires a lot of dedicated equipment, and the wastewater operations branch operates 16 Vactor combination trucks, primarily on Volvo chassis.

To reduce future problems, the city has changed design guidelines to require more slope for new lines. Cleaning is still largely reactive. “It seems like we’re always catching up with normal maintenance, and responding to customer complaints, but we are now doing preventive maintenance near apart-ment complexes, and we’ve also agreed to routinely clean lines adjacent to recurring SSOs,” Gee says.

The city isn’t using GIS to track and schedule maintenance, but is starting to track and map SSOs for reports, Gee says. “We track SSOs monthly, and we were diminishing the number per mile steadily, right up until Hurricane Ike. We started losing the battle again after that, and we’re not sure why. We know a lot of our existing siphons stopped working, and it could also be debris buildup.”

Looking carefully

The city inspects systematically and is now archiving more than 100,000 videotapes. “We think we can do better with DVDs,” says Gee. “They’re easier to access and have better shelf lives.” VCR tapes and DVDs receive a barcode, then are indexed in a TV tape database. The TV inspection information for each mainline (manhole to manhole) section, including the actual report, is available in the city’s Infrastructure Management System (IMS) database.

The city once had permanent flow monitors installed but removed them when the costs of maintenance and monitoring seemed to outweigh benefits. Now, the city occasionally hires contractors to gather data as needed.

On a daily basis, the city operates one to four high-cube TV inspection vans. These are equipped with CCTV equipment from CUES Inc. and cameras from RS Technical Services Inc. The cameras are single conductor, low-light units with auto focus and auto iris, pan and tilt, and 360-degree rotating head. The transporter is a motorized mount that is height adjustable for negotiating and inspecting 6- to 30-inch pipes. The video cable reels can hold up to 2,000 feet of armor-clad, single conductor cable. Typical mainline sections are 250 to 300 feet long, but crews can televise up to 900 feet in a single setup.

Houston has experimented with other methods of grease reduction without notable success. “We’ve experimented with solvents, and we had a contract to use a bacteria system,” says Gee. “Something called a Bio-Sock was used to drip bacteria into the system. I think it had some limited success. The branch is now talking to vendors about bacteria, enzymes, and other FOG-removing products.”

Overcoming challenges

When it comes to sewer stoppages, Houston has not been blessed. Flat terrain, predominantly concrete pipe, and high temperatures cause chronic problems, and the occasional hurricane or tropical storm doesn’t help. But with steady appeals to the public, consistent cleaning and rehabilitation of lines, and a willingness to consider different technologies, the city is slowly but surely winning the struggle.