"We take every opportunity to reduce our carbon footprint, by adopting the most effective best practices out there in the industry.”

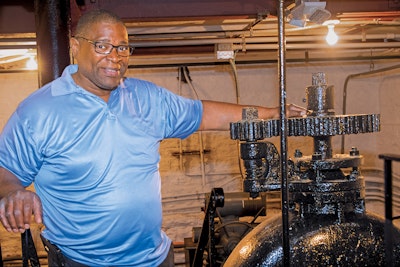

That’s Norman Jones, Environmental Services commissioner, describing the mission of the Rochester, New York, Bureau of Water, which serves...