Interested in Stormwater?

Get Stormwater articles, news and videos right in your inbox! Sign up now.

Stormwater + Get AlertsFor years, residents of a historic neighborhood in Charles City, Iowa, endured street and yard flooding after rains of one inch or more. Instead of installing new streets and storm sewers to solve the problem, city officials chose permeable pavers.

Now, 154,500 square feet of attractive concrete paver-block roads line 17 blocks of this city of nearly 8,000 residents. The paver system naturally collects and filters stormwater runoff, reducing loading to the storm sewer system.

“People at Unilock, which manufactured the pavers, tell me this is the largest residential retrofit permeable-paver project in the United States,” says Eric Otto, a civil and water resources engineer at Conservation Design Forum of Elmhurst, Ill., which designed the project. “This installation achieves zero discharge with up to a two-year rainfall, which is three inches of rain. That’s a big reduction in the load conveyed by the existing undersized storm sewer system.”

Even with a 10-year rainfall, the $3 million paver system is designed to reduce runoff by more than 60 percent and decrease peak discharge by more than 90 percent. In addition, the system effectively filters pollutants, which adhere to the stones below the pavers until microorganisms break them down, says Tom Price, principal water resources engineer for Conservation Design. That helps protect the Cedar River, which runs through the city and is a vital resource.

Natural drainage

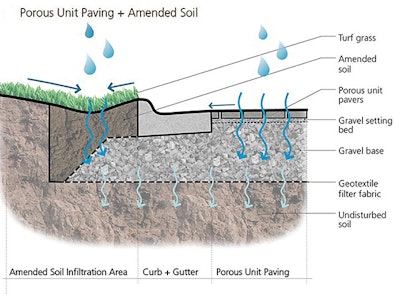

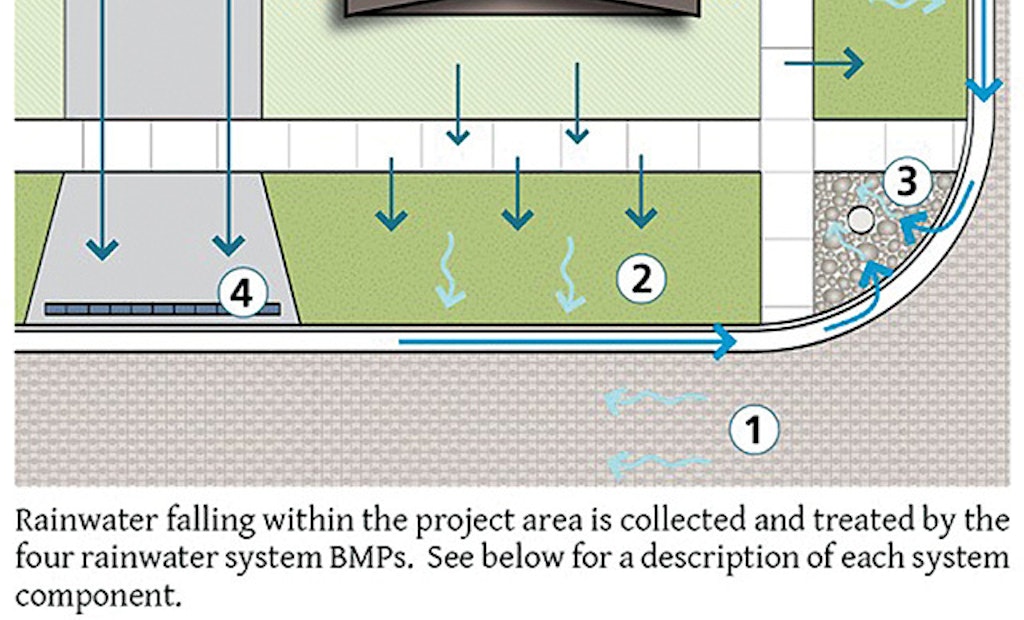

Permeable interlocking concrete pavement (PICP) consists of pavers separated by joints filled with small stones. Water flows through the joints and into layers of crushed stone. The voids between the stones hold water while it percolates into the soil below. Voids make up about 30 to 40 percent of an installation, says David Smith, technical director for the Interlocking Concrete Pavement Institute.

From bottom to top, the Charles City installation consists of a layer of woven polypropylene geotextile, two feet of open-graded 3/4-inch stone, a 1-inch-thick setting bed of open-graded 3/8-inch stone chips, and 3 1/8-inch-thick precast concrete paver blocks rated to handle more than 8,000 psi, with a 50-year lifespan.

Sandy subgrade soil in the area enhances the paver system’s performance. The installation also uses parkway bioretention swales that absorb runoff from house roofs, sidewalks and front yards and trap sediment that could clog the paver system. In addition, cobble infiltration areas in the triangles created by sidewalks at intersections capture curb and gutter runoff.

Years of flooding

Completed in November 2010, the paver system eliminated flooding. “People experienced a lot of ponding in their yards,” says Tom Brownlow, city administrator. “When that part of town was developed, storm sewers weren’t common, so sections of it have no storm sewers. In other parts, the sewers are undersized. Plus, the roads had a big hump in the middle, thanks to multiple recoatings. Sometimes the road was higher than the front yards.”

When Brownlow was hired in 2006, the flooding was a top issue. The city considered installing a new storm sewer system and building new concrete roads, until Brownlow saw a representative from Conservation Design give a presentation about permeable pavers.

He found them attractive because they addressed both road deterioration and flooding, and were environmentally friendly. “We want to do the right things environmentally, and this treats water naturally,” he says. “It goes back into the aquifer instead of flowing back into the river.”

Stimulus funds

Federal economic stimulus money and a $100,000 grant from the state paid for nearly 25 percent of the project. A state loan financed the rest, and it will be paid off in no more than 20 years by revenue from a 1 percent sales tax. A new concrete road and storm sewers would have cost about 30 percent less, but on average, pavers are more durable and require less maintenance.

“Also, if we put in a conventional concrete road, all that water runoff goes into stormwater mains, which means we’d have to upsize the storm sewers downstream,” Brownlow says. “That’s one thing the cost comparison ignores. It came down to playing it safe versus doing the right thing, and it has turned out really well for us.”

Comprehensive education, including public meetings and explanatory stories in the local news-paper, helped ease any concerns. Residents clearly enjoy their beautiful new streets and water-free yards. “It looks so attractive that people in other parts of town are asking if we can do the same thing in their neighborhood,” Brownlow says. “Some people even want to do their driveways with permeable pavers. It’s kind of neat that they’re embracing the technology.”